‘Birding’ is a term Garrett has repurposed to define his preoccupation over the last two years. His meaning bares no relation to observing rare birds through binoculars; rather, it describes his video editing technique of painstakingly omitting the many crows, ravens and seagulls from scenes in Alfred Hitchcock’s cult thriller ‘The Birds’. In all Garrett’s recent exhibitions, he reveals further glimpses of the modified film, his acute understanding from countless viewings almost as razor sharp as Hitchcock’s. At Brigade, peering from behind a large theatre curtain, is an edited excerpt from the film’s chaotic climax, foregrounded by a series of prints in the main galleries.

Other work in previous shows comes in a variety of media. Instead of conventional pigments, Garrett applies found photographs on large-scale paintings, which he appropriately names ‘Picture paintings’ – he soaks and rubs away layers of film, turning it into a pliable pulp and then daubing it onto canvas. In ‘On Photography’, essayist Susan Sontag wrote that, ‘the painter constructs, the photographer discloses’; yet in many of Garrett’s pieces, he does both with equally elliptical outcomes.

Here, seemingly innocuous snapshots from 'The Birds' line the walls of the gallery. Printed onto textured etching paper, the surface is reminiscent of his photo rendered paintings, each arrangement like a film reel of climactic stills. As in his reworking of the film itself, the birds are missing, their omission bringing to fore quotidian backdrops – a dinner table, or bright skyline, for example. A further array of montage prints, each replicating a second of footage also adorn the wall, reminiscent of artist Sophie Calle’s studies of hotel rooms from the 1980s.

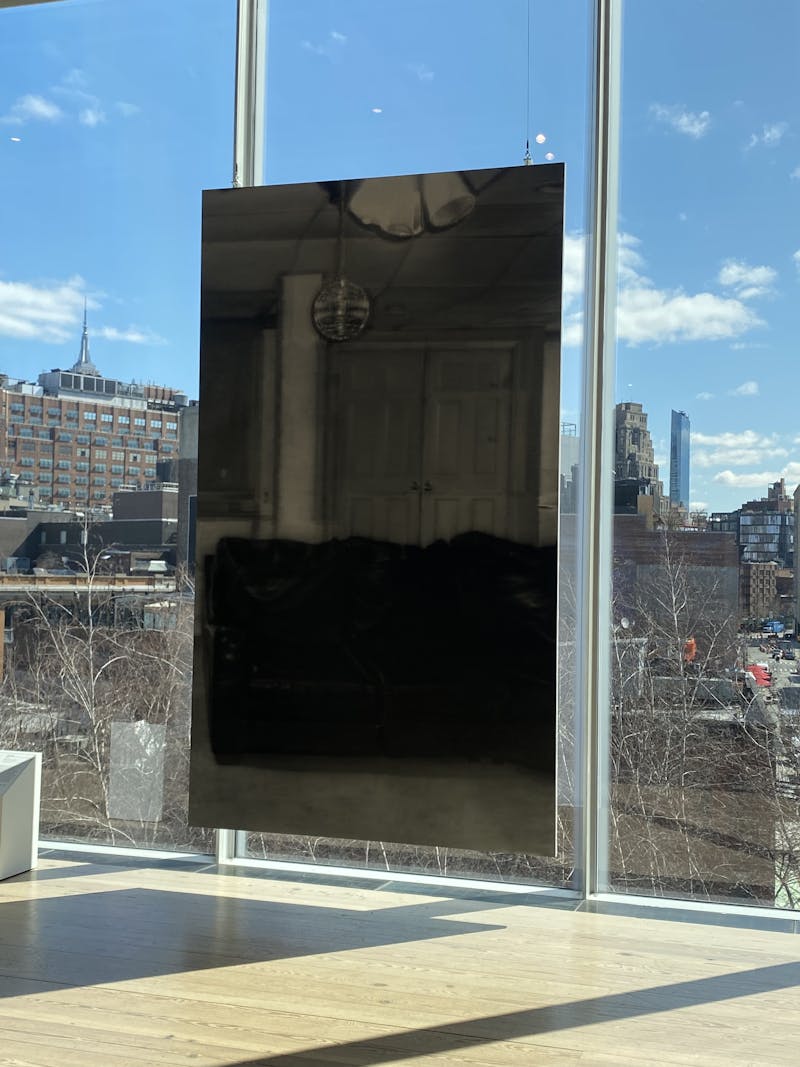

Garrett Pruter, The Birds, 2023

While video editing, Garrett embraces his imperfections. You’ll notice in his film how faint spectral shadows of birds often flitter on the screen while people clamber for cover. Writer Janet Malcom wrote that 'all the canonical works of photography retain some trace of the medium’s underlying, life-giving, accident-proneness.’ In Garrett’s film, we notice these almost like the blurring effect similar to remnants of stains from rubbed-out graphite on a sketch or study. He likens the technique to painting, ‘embracing the hand and the marks left behind’, by using his stylus as if it were a brush on canvas, isolating areas frame by frame and shooing away each bird. In Hitchcock’s original, the editors used compositing methods of layering frames together to create the illusion of huge flocks of birds, which as Garrett’s sharp eye has noticed, reveals similar accidents and errors to his in removing them.

His approach to sound editing treads a similar path. Using audio recording software, Garrett chops up the score of people’s screams and removes the bird sounds entirely. He then resamples these fragments during the scenes with the birds omitted. Our expectation is continually questioned, as protracted scenes of dialogue build more suspense. Where the ambushing birds in Hitchcock’s provoke a furore of wailing and fear, in Garrett’s he notes how the birds’ absence becomes ‘a placeholder for any type of collective fear’ as protagonists hysterically gesticulate at nothing – their apprehension imitating our own as events frantically drag out. At Brigade we’re fed glimpses of a much broader genre of trepidatious horror. Voids, in Garrett's world, become the real villain.