Collecting – it’s a curious and instinctive process. I’m writing this in autumn, the crimson leaves quivering on their branches, trembling as they trickle to the ground. An eager girl runs past me, her hands clasping a selected bunch of maple, birch and hawthorn. Her impulse to collect these minuscule markers in time – just as I often pocket shells at the beach – is reflective of how nearly everyone impulsively assembles things to preserve memories for longer. To cherish them and make the good feelings last.

As giddy as the leaf-bearing child, Nat Faulkner has been obsessively collecting cigarette cards on eBay. From 1875 to the 1940s, these humble cards, no bigger than a matchbox, were placed inside individual cigarette boxes by tobacco companies, marketing devices to promote brand loyalty. They’d be arranged by category, the imagery often depicting broad, random studies of popular interest from the time, each meticulously drafted by unnamed artists: ‘Weapons of War’, ‘British Butterflies’, ‘Head-dresses of the World’, ‘Swimming and Diving’. Drawn to their lure as prints in their own right, Nat appreciates them all the more for their seeming desire to categorise all human endeavour with their arbitrary taxonomy.

He wanted to investigate the use of words in illuminating the cards, ‘unpacking’, as he calls it, the scenes of his own sprawling collection. He fixed on the use of homographs – words that share the same written form as another word, but have different meanings and pronunciations. Inspired by Raymond Roussell’s Impressions of Africa – a book of poems where an anonymous artist was commissioned to make illustrated responses – and Rene Magritte’s Key to Dreams series, in which paintings of everyday objects are labelled with frivolous associative caption, Nat considered how a single word influences the understanding of the card’s image. As if playing a game with himself, he’d lay out a list of words, merging separate collections with each homograph, then repeating the process 25 times. Marcel Duchamp, also a game enthusiast, chose his synonymous readymades ‘based on a reaction of visual indifference’, a ploy Nat adopted too: both the word and the image gain a new perspective under differing pretences.

Box design by Piotr Jarosz and Numbered Editions

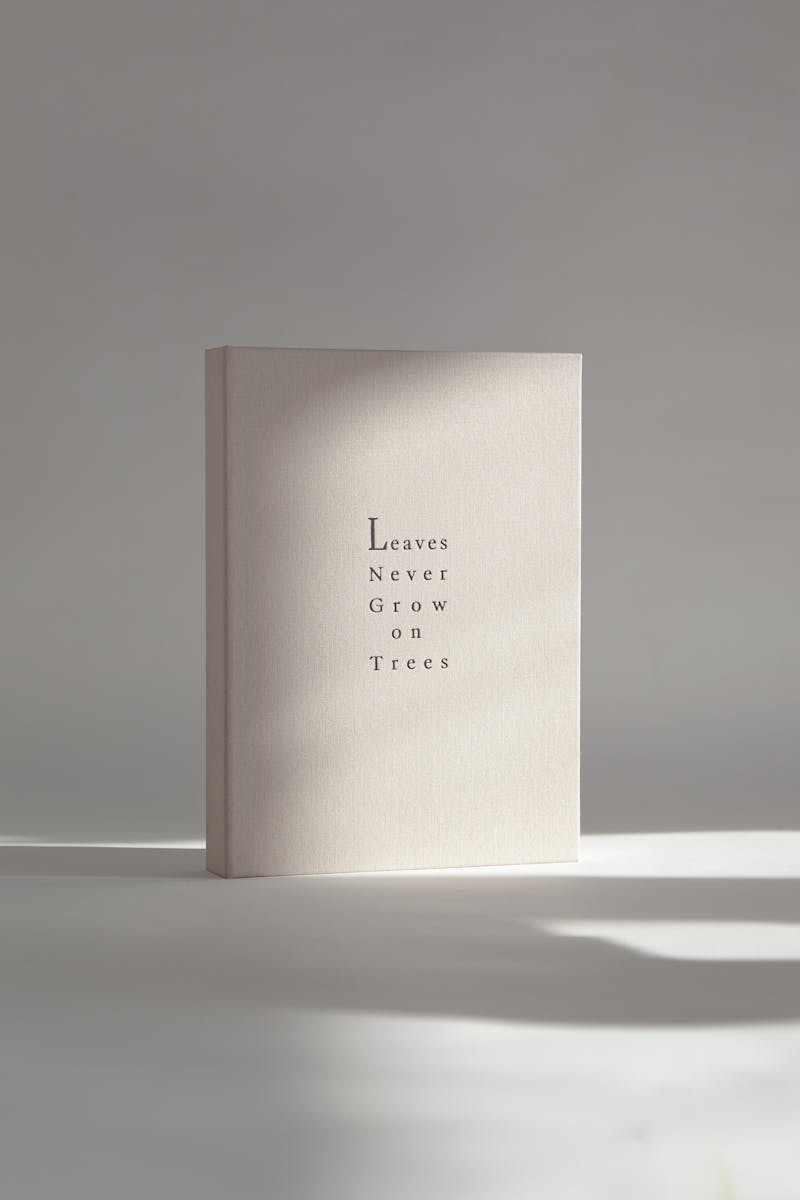

The title of the box, Leaves never grow on trees, is pulled from Jean Arp’s book of automatic writings adorned with rubbings by Max Ernst. Nat was drawn to the title for its paradoxical and banal logic. The pages, or leaves, inside the box you’re holding are intended to be appreciated in a similar way. There’s a feigned rationale at play – each page is presented in the traditional way of displaying collectable cards, with eight 45 degree cuts to hold them; yet the words underneath demand scope for your mind to dig deeper, to look closer. It’s a game where you get to pretend to be a surrealist taxonomist.

Installation view: Leaves Never Grow on Trees at South Parade

Installation view: Leaves Never Grow on Trees at South Parade