In the first stanza of Roger Gilbert-Lecomte’s poem ‘The Black Bull’ he describes a puppet ‘with a face of chalk and eyes of crushed brick’. Oliver Bak’s drawings, with his protagonists forged in ghostly white crayon, refract the avant garde French poet’s looming spirit. He stumbled upon a copy of Gilbert-Lecomte’s ‘Caves en plein ciel’, or ’Caves in the sky’ by chance, initially enchanted by the title’s surrealist analogy. As he made the series, Oliver envisioned him as a kind of invisible friend, his affinity with the poet’s eclectic metaphors permeating through the pencils in his palm.

Oliver is best known for refulgent, monochrome paintings depicting figures and fauna appearing behind veils of forestry. You can’t help but see in his paintings the flamboyance of such masters as Odilon Redon and Gustav Klimt with their ceaseless storytelling evoked seamlessly into every picture. Quite often Oliver’s scenes become clearer after numerous returns, the ghosts of his initial marks reappearing behind trails of impasto paint in subtly differing tones. The critic Brian Dillon, when writing about painting and erasure, noted that, ‘whether rubbed away, crossed out or reinscribed, the rejected entity has a habit of returning, ghostlike: if only in the marks that usurp its place and attest to its passing.’ In Oliver’s four paintings shown alongside his drawings we witness life and death together, ‘Crystals’ and ‘Caving in’ are foxed with blemishes alluding to the growth of mycelium on a dying tree, while in ‘The Sleeper’ and ‘Son of Bone’ morbid figures emerge from pointillist flecks of paint that seem like particles of mould. Each are cast under similar blotchy brushwork, the spirits mingling from each painting to the next.

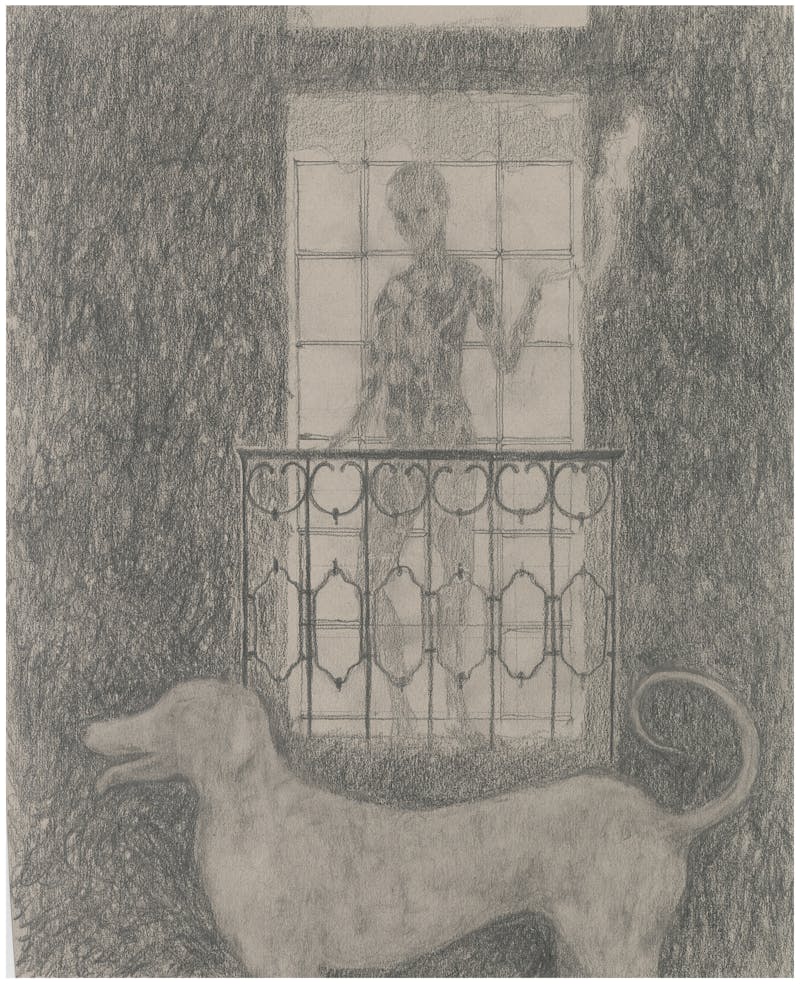

But it’s his drawings, a medium which is usually only familiar to Oliver when making preparatory sketches for paintings, where these omnipresent ghosts become more glassily translucent. In a similar monochromatic vein to the paintings, he works on grey paper, the silvery graphite of his pencil and fingermarks leaving imprints like the spectral remnants of a haunted spirit. He notes of the dark and chilling mood Gilbert-Lecomte’s poems evoke – ‘a home to ghosts and to the children of night’, ‘in a cloak of pale shadow, cold dawn’. Oliver’s drawings are seemingly frozen in time, as his downcast figures are either stripped to their bare bones or submerged in the depths of nature. The fragility of life is hard to ignore, as characters are directly confronted with their own death, in ‘Sarcophagus’ the outline of a foetus reveals a skeleton of the unborn baby.

Oliver Bak, The Smoker, 2023

Oliver says that ‘he can’t hide with drawings’ as every contact from his pencil relies on assurance, rather than the endless deliberations his brushes perform on canvas. He harnesses the will to scrape away or over-paint areas while wet, using the smudges of his grey-daubed fingers to evoke the depth his bristles achieve in his paintings. Flowers find their way into most of the drawings too, tangled among the thick hair in ‘Float’ or in ‘Vacancy in glass’ dried poppy seeds become like floating balloons behind a sleeping figure, both perhaps reminders that even in from death, new life can still bloom. Flowers are often given to celebrate the birth of a newborn, or console after the death of a loved one. Whether painted or drawn, this disparity of life and death seems to always find its way into his work. He recalls Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s painting ‘The Roses of Heliogabalus’ from 1888, in which guests are buried to death in an abundance of pink violets.

Roger Gilbert-Lecomte’s life was marred by a sickly addiction to morphine that would lead to his death aged 36. In Oliver’s sketch, the poppy seeds that constitute the drug are almost like floating guardian angels leading his cadaver into the the sky. While not all of his drawings nod this overtly to the poems, Gilbert-Lecomte’s words invariably flitter through Oliver’s synapses. Leonardo da Vinci famously wrote that ‘painting is poetry that is seen rather than felt, and poetry is painting that is felt rather than seen.’ Oliver, however, works the other way around, his artistic impulses evoking the very aura of the poet writing at his desk – making indelible the words which Gilbert-Lecomte never got to fully conclude.