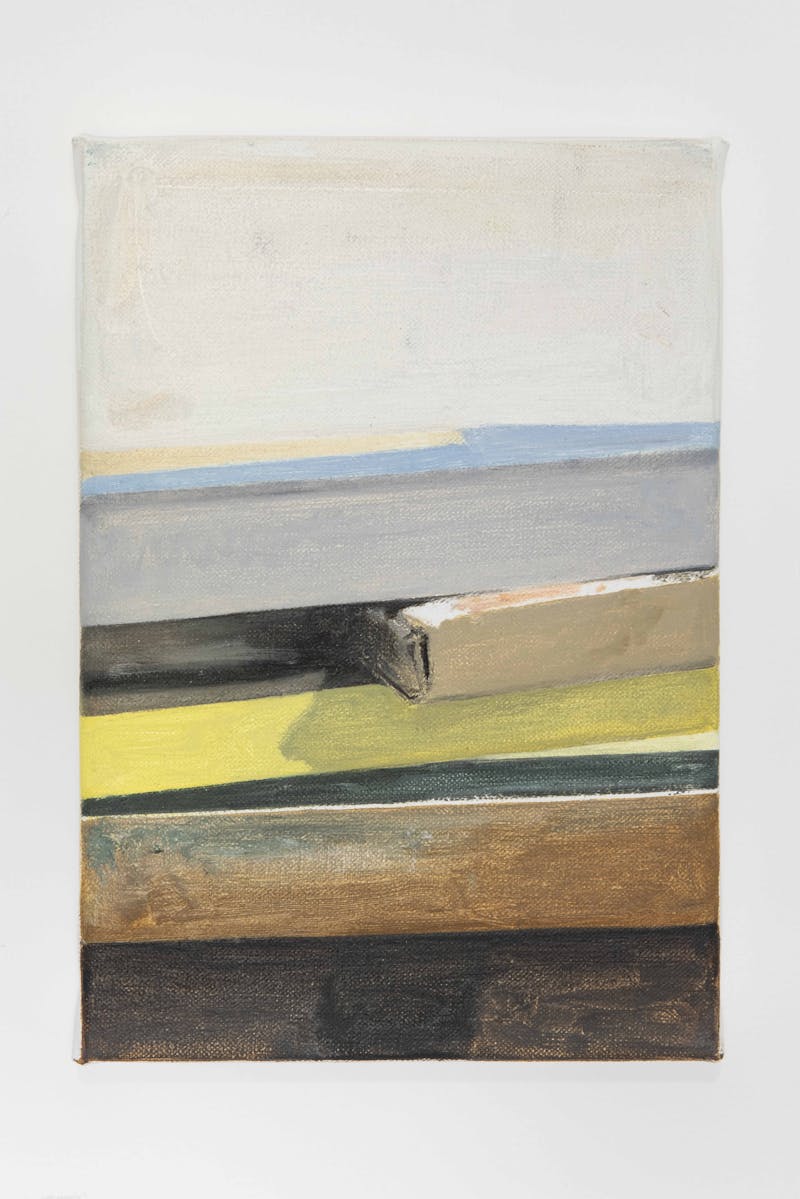

Ian Homerston, Untitled, 2021

The first Painters Painting Paintings show features a painter who paints paintings of his own paintings. Ian Homerston doesn’t look too far for his inspiration: just across his pocket-sized studio in rural Kent, at his stacked-up canvases. In Paintings, his paintings give centre stage to the edges of other frameless paintings: since graduating from the Royal College of Art in 2009, he’s spent a decade ruminating on the sides of his paintings – the fringes, the borders, the overlooked – and this show spans two years of enquiry. The paintings are rarely much bigger than an envelope, and so are almost life-size when viewed on a laptop.

For Ian, the edges of paintings have become more compelling than the intended fronts. The remnants of muddied marks, splodges, smears from his painty fingers: they speak of time spent cogitating in the studio. They are the unintended artefacts and proof of long industry, and Ian began painting paintings of them to memorialise these inadvertent moments.

But, of course, intention soon shoulders its way in. The compositions, for example, are hardly accidental. Ian constructs irregular stacks of paintings into still lives, the bigger canvases jutting out, leaving pronounced shadows for him to refer to. After drawing outlines, he’ll make deft marks with a brush, commemorating the edges, sometimes exaggerating the shadows for depth. Using a mixture of sable and hog’s hair brushes while vacillating between working flat on the table and upright on the wall, he’ll mix his oils with sansodor – a non-odorous turpentine-like medium – to make the surface dry and subdued. Ian tends to heighten reality by abstracting the colours he uses to paint shadow, these choices, an intriguing commentary on the original choices on the paintings he is painting. He realised after years spent studying the edges, how much darker and muddier the tones were than the whites and neutrals he’d initially assumed. The more you look, you’ll notice washes of yellows, blues and browns he’s applied to illuminate the outlines. Ian takes inspiration from Belgian artist Raoul De Keyser, emulating his love of the everyday rendered into simple, boundless abstracts.

Installation view: Ian Homerston, Paintings

Another of Ian’s inspirations are the still lives of Italian painter Georgio Morandi, and the sense of timelessness in his work, the product of a long career spent looking at the same vases, bottles and jars. Ian contemplates his collected canvases as if they were as quotidian as Morandi’s vessels. Which of course, in an artist’s studio, they are. Ian’s piles of paintings accrue over time, growing and teetering, the consequence of his other work – paintings of trees, windows and fences. Borders, too, in a way: edges which define the entity they contain and where art (and so much else besides) begins with an outline.

There’s no rigid routine to his painting. It’s a much more loose and unfurling process. Ian spends time considering his subject. He’ll then tend to paint quickly, not lingering for long. Before picking up his brushes he takes cursory photographs of the stacks from different angles. Ian notes that, when he begins to paint, ‘the process of editing tends to happen on the canvas' rather than from life. Once he stands back, deeming it complete, he’ll rarely return to work on them again, preferring to store them among the more awry and less staged stacks of small paintings in the studio. Stacks which, funnily enough, he doesn’t paint.

As we discuss the self-referential nature of his paintings, Ian shows an image of a box of tissues. In the photograph is a logogram of a hand drawing a tissue from the box, printed on the box itself. Ian notes how paradoxically unnecessary but psychologically reassuring the icon is. It’s a consumerist tactic – looking at the box, we can’t help thinking about ourselves as we imagine replicating the action of the image. Ian’s paintings do something similar: they make you want to turn the canvases around and see what’s on them. Resisting the elucidation of the allusive title, Paintings is a show of paintings that chooses not to give a steer to the viewer. It’s rare that something so literal can feel so challenging, prodding observers to construct their opinions about the work that is shown, and the works that are concealed – a blank canvas, almost. Except these canvases, with their colourist beauty and formality, are anything but blank.

Ian Homerston, Untitled, 2021