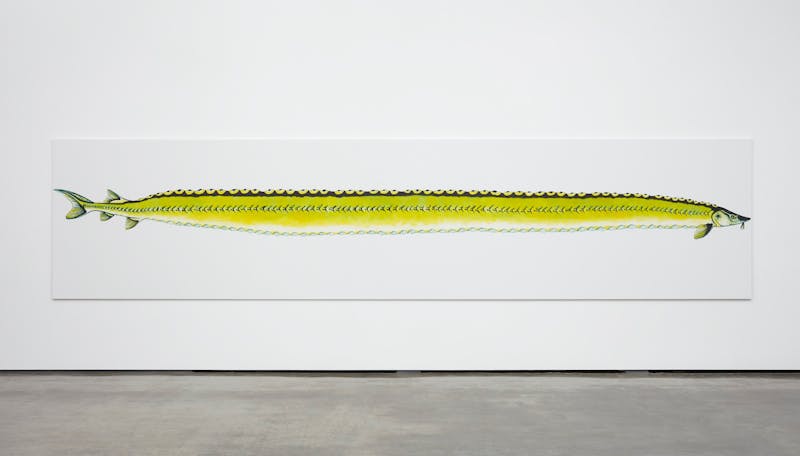

Like trying to follow the flits and surges of a dragonfly, Calvin Marcus is so mercurial you never know what he will do next. His paintings fluctuate in appearance, never knuckling down on a style for too long before darting off in the opposite direction. It’s refreshing as a bystander to witness this bohemian approach in an art market that famously demands a consistent flow of bait for hungry collectors to feed on. Appropriately, Marcus made a seminal series of paintings called Stretch Sturgeon, the fish whose eggs are consumed as caviar. Was this some kind of metaphor for the all-consuming art world? Only he knows.

It was these memorable paintings that were my portal to his effervescent art. Painted on four hulking 7m-long canvases, stretching the walls of the gallery, they simply refused to accept inattention. Most of Marcus’s paintings do that: full of cheek, satire and sarcasm. Each of the series innately impacting on first glance – if they were novels, they’d be described as ‘unputdownable’. In City Pig/Wild Boar his fictions merge flawlessly on the canvas: a pig is sat cross-legged reading the New York Times, next to a boar wading through overgrown grass. Marcus has this unusual ability to suck you into his vortex of incongruous tales, where elongated fish and reading pigs are quotidian. A rowdy snort of laughter was my first reaction.

As well as hefty painted canvases, he often dabbles in sculpture, once littering an entire gallery floor with hundreds of plumbing pipes painted pink to resemble squirming intestines. In Green Calvin and Blue Devil he merges the two seamlessly – small reliefs of ceramic heads lay plonked on top of hardboard, camouflaging into the paint behind. The heads jut out awkwardly as if they could roll off and smash on the gallery floor. Marcus is constantly teetering between these frictions and contradictions: testing the limitations of a gallery like a precocious schoolboy outsmarting his teacher. I like to imagine the conversations that might prevail in planning a solo exhibition of his: ‘Will the paintings even fit through the door?’ I pity the poor person who has to run the risk assessment. But it’s precisely his bravado that has cemented his reputation as one of the greatest artists of today. You never know what you’re getting, and if you do it’ll likely arrive with an added surprise.

Calvin Marcus, Stretch Sturgeon, 2019

Marcus is unmistakably a very skilled painter, too. So adept he can vacillate between fastidious detailed work and more gestural mark-making, yet be as convincing at both. In Los Angeles Painting and Conspiracy of Asses the painting application is much more photographic: the sharp, definite lines are so crisp they leave little to the imagination. He mostly paints using watercolours, favouring the washy tones which seep quickly and deeply into gesso-primed canvases. Los Angeles Painting is one of Marcus’s more minimal efforts – a large depiction of a windscreen mirror reflecting a barren red vista. Such is his game-playing the painting itself doubles as a windscreen, a porthole for viewing his busier paintings more deeply.

You might stumble across his oil bar paintings and assume, as I did, that they were made by a different artist all together. He’s good at that, Calvin. Glaringly different in style but equally as large in scale, Dead Soldier and me with tongue are some of the more unruly in his collection – a far cry from the intricate aliases he sometimes adopts. Like drawings from a sketchbook, only rendered huge, there’s nothing inconspicuous about their content either. In me with tongue Marcus as a caricature is painted pulling a feral face with his tongue out, and in Dead Soldier a porcine commando, lays dead with the same protruded tongue. They win you over with a peculiar kind of delight few other painters can command. That irrepressible sardonic Marcus cheek. Both paintings were displayed amongst a series of counterparts on the walls, like giant pages from a cut-up comic strip. Their sheer intensity, the Dead Soldier painting being almost three metres tall, looms over you like a scene from a haunting dream. They leave you both confused and captivated. As the best art should, right?

Recently, Calvin has skittered away in a new direction. Extrapolating on a painting of a houseplant he made in 2020, Begonia, his recent exhibition – HER at Clearing in Beverley Hills – presents six paintings of a leaf from differing angles. Painted with a distinct colour palette of greens and reds, the leaf’s veins, stem and stipules are handled with the deftest of brushwork, a real treat for the eyes. Whatever Marcus paints, whether homespun or wacky, he does it with a finesse and coolness which separates him from the rest. He’ll always trick you, lead you astray for a moment. But you always come back for more.