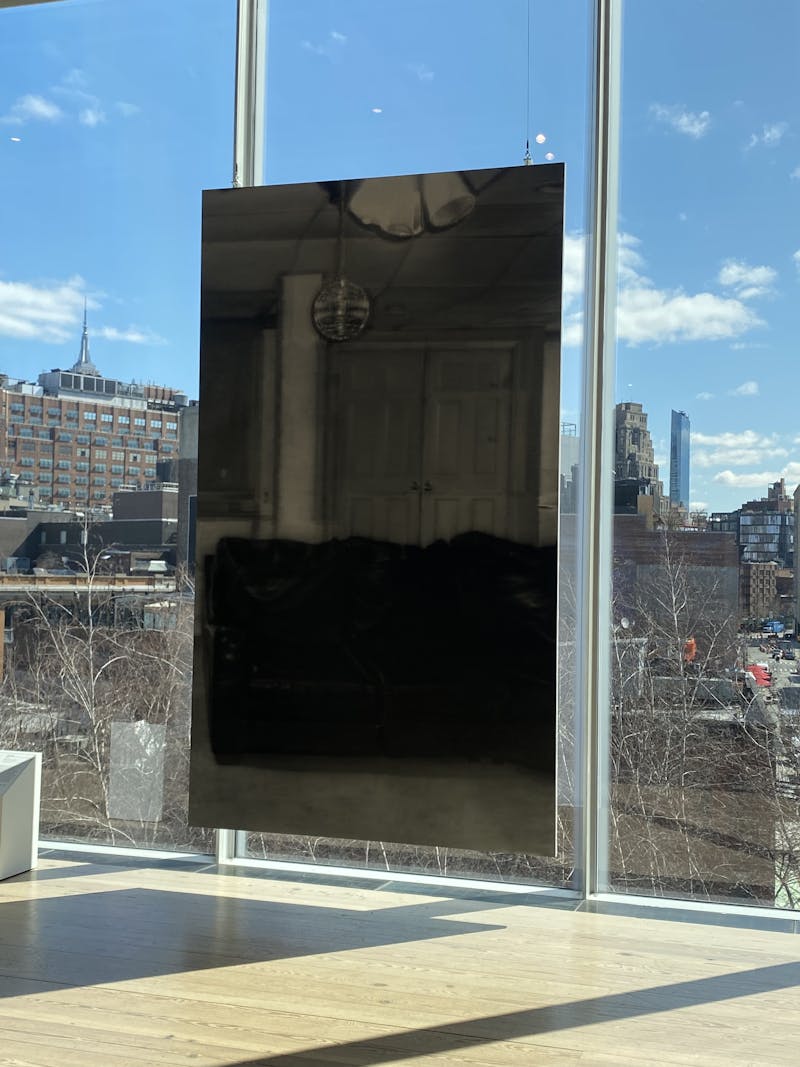

Nathanaëlle Herbelin, Military Training Zone, 2018

At almost every moment of the day, Nathanaëlle Herbelin paints. She paints, and she sleeps. For her, painting is as much a part of living as cooking a meal – which, funnily enough, she’ll often do at the same time. Painting follows her like a shadow, only leaving at the dead of night. Her compulsions to paint rarely leaves: a portrait of a friend lying on a sofa, a painting of a bowl of eggs – her lens never warps reality or strays from the truth, however homespun. Working in between studios in Paris and Tel Aviv, her paintings strive – and achieve – an honesty, an openness, calling to mind the observation of French novelist, George Perec in Species of Spaces and Other Pieces (a book Herbelin often returns to): ‘But how should we take account of, question, describe what happens everyday and recurs everyday: the banal, the quotidian, the obvious, the common, the ordinary, the infra-ordinary, the background noise, the habitual.’

Knowing this calm frankness is at the heart of her work prompts a surprising reaction to her exhibition for Painters Painting Paintings: shock. Temptations of positioning are landscapes Nathanaëlle painted in 2018 during a residency for the Arad Contemporary Art Centre in the Negev desert, nine years after her obligatory military service as a tour guide in the same area. These five paintings are Herbelin’s broad views: tracings of her own experiences in the desert and documentations of its habitants a decade on. Foxholes and bunkers pockmark the ancient rocks and dunes, scenes of dispute since Biblical times and before. Yet these are also the places Nathanaëlle visited as a child, first seen from the backseat of her mother’s car on family trips from the village of Zoran where she grew up. The title refers to her pondering on where to situate herself – literally and politically – picking out indications of life in the desert, from military installations to the aftermath left behind by desert ravers. She chooses to look on from nearby hillsides, the optimal distance for painterly perspective, and, out of humility, at an arm’s length from the tumult. These are paintings which take the long view.

Nathanaëlle Herbelin, Délet, 2018

Just as a photojournalist would document with a camera, Herbelin does with her brush, mindful of the stark photographs of apartheid South Africa by artist David Goldblatt. At 5am, as the early sun rose and before her daily duties as an excursion guide in the army began, she trekked with her paint box to a hill to record the landscapes beyond, taking the odd photo for reference. She returned to this routine during her residency. While she worked Herbelin often reflected on the detailed drawings of the hills in Jerusalem by Israeli painter, Anna Ticho. As an observer, conscious of her past as a conscripted defender of the Occupation, she wanted to understand the array of desert habitants: Bedouins, Kibbutzniks, Palestinians, Armed forces, and now ravers all laying claim the same plot of land. Painting – or recording, as Herbelin puts it – is a way of ‘showing all the habitants and the differences between them’. She’d sit faraway enough to not invade anyone’s privacy – often Bedouin families would request no photographs be taken – but close enough to see something true and allow her to paint. On occasion, seeing what she was doing, she’d be asked to paint a portrait. While the sun would burn down on the desert, she’d spend hours recording sights, as if looking through a camera and clicking the shutter with paint, the surge of unbearable heat making it impossible to paint for longer than a few morning hours. She’d often return to her paint box again in the evening once the sun was slinking out of sight to finish what she started, before sleeping under the stars.

Painted on wooden boards, Nathanaëlle mixes a range of turpentine, linseed and vegetable oils with her paint, which she likens to the slow geology of the desert. Herbelin commemorates this geology in her paintings: in some, the surfaces look puckered and dry, as if the paintings themselves have endured a pelting from a sand storm. Others are wet from layers of rabbit skin glue and a natural primer, which, like the desert sand, is high in calcium. This emulates the effect rare rainfall has on desert soil when the water sinks into the sand before slowly evaporating to form a calcium called caliche. You’ll notice small bubbles and divots that resemble the textures of the desert rock which she’d perch on as she painted. Her washy oil paints blend and merge; sometimes the brush marks are visible over eroded down blisters on the surface, which she degrades using coarse scraps of sandpaper. Often the abrasions she makes will be vehemently scratched at, out of anger towards the needless constructions being built. The Egypt–Israel border, instigated by the outgoing Israeli hardline Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in 2011, is one she plans to paint soon. Painting for Herbelin is like writing a diary – attempts to portray what can’t exactly be seen on camera or write in words. She paints what she sees, as they are, as they feel, as uncomfortable as the truth so often is.