‘Education is the point at which we decide whether we love the world enough to assume responsibility for it and by the same token save it from ruin which, except for renewal, except for the coming of the new and young, would be inevitable’.

— Hannah Arendt, Between Past and Future, 1961

Teaching has moved to Zoom; the grid of faces like in an episode of American sitcom The Brady Bunch, but for the few stragglers who appear simply as letters, as if tiles in a game of Scrabble. Waving goodbye after finishing a seminar – or, in the ugliest of coinages, a webinar – my tutor replied: ‘I don’t wave at the end of Zoom meetings’, before closing her laptop screen. In a video call, the smallest interaction, or lack thereof, usually followed by a ubiquitous glitch, can feel catastrophic. Why is that? It’s because talking at a screen makes us feel exposed and, therefore, under threat. There are entire forums dedicated to dealing with Zoom anxiety, and a study in Germany showed that delays on the line of just 1.2 seconds made people perceive the responder to be unfriendly.1 With the software now catering to a ludicrous figure north of 300 million users worldwide and claiming to ‘keep you securely connected wherever you are’, is it time to quell our exuberance and reclaim our inhibitions, even if we risk falling into Arendt’s ruin?

During our honeymoon with Zoom, we chose captivating backgrounds and applied fashion designer Tom Ford’s instruction to elevate the camera and put a lamp behind it so that we would look our best.2 I was pleasantly surprised with the high standard of online teaching. I would flood my days with lectures by critics, attend studio visits with artists and plaster my walls with fastidious notes and mind-maps. I felt as engaged as ever I would be in reality – maybe more so. As a Zoomer – the slang term for Generation Zs born in the 1990s – I was living up to my epithet and wearing it proudly.

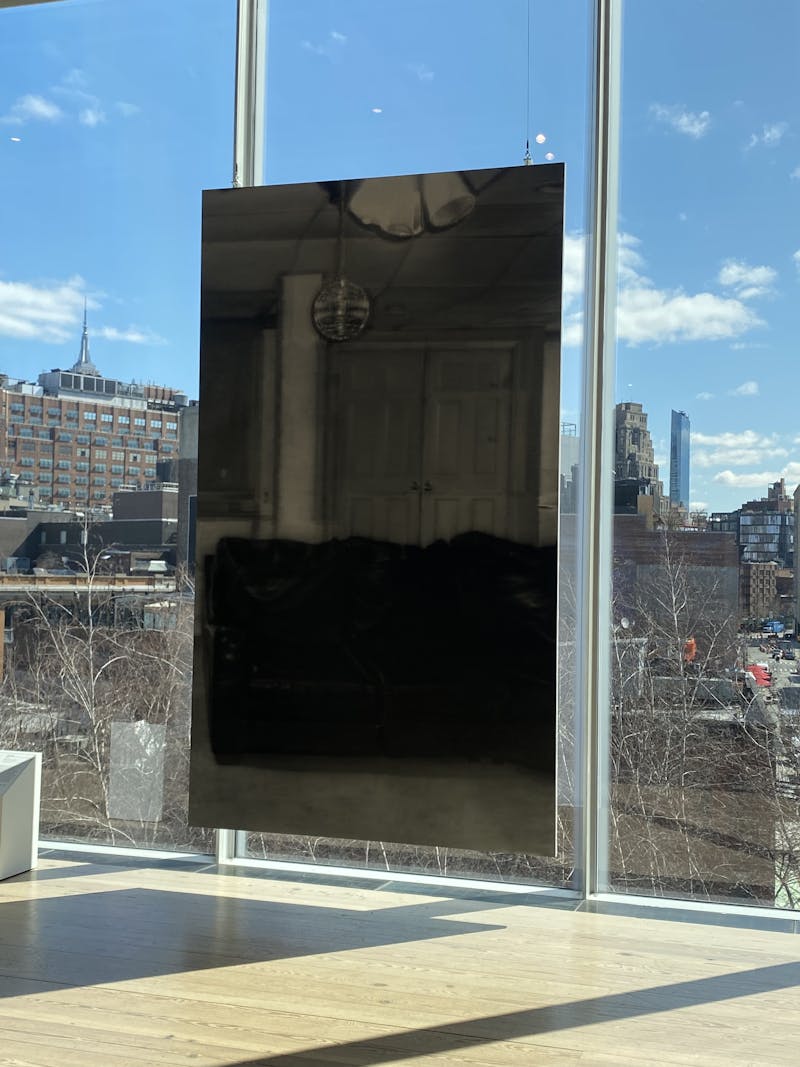

Studying for a master’s in Curating Contemporary Art, my career choice often induces some bewilderment. This is made evident by the range of job titles that the term ‘curating’ encompasses: ‘editor, DJ, technician, agent, manager, platform-provider, promoter and scout, or – more absurdly – as diviner, fairy godmother and, even, god’.3 Another preconception for many is that curating is unteachable (or pointless) and for some, like curator Jens Hoffman, it remains a mystery why anyone would study it over literature, philosophy or art history.4 After weeks of Zoom learning, it dawned on me just how much my passion relies on human contact: walking through exhibitions on my own two feet, rummaging through artists’ works in their studios and not having to take endless blurry screenshots – essentially, seeing things with my own eyes.

I’ve begun to fear that all I‘m learning is how to curate intriguing bookshelves for Zoom backdrops. It seems I'm not alone: life-long bibliophile Thatcher Wine has made a career from curating bookshelves for celebrities, Gwyneth Paltrow among them, and has been earmarked as one of the new luminaries of the Zoom boom. He’s quite convincing too, if a little romantic. In a recent interview for Penguin, he discusses his top tips for book curation: ‘Think about what exactly you want to convey about your interests, your hobbies, how well-read you are, and also how organised you are. Then, take everything down to start with a clean slate, dust them off, and say, If I were a stranger, what would I think about me by looking at what's behind me?’5 Whatever happened to not judging a book by its cover? We are now, thanks to Zoom, judging people by the book covers they keep.

The Brady Bunch, 1970

Months on, Zoom fatigue has kicked in. University life has become more oppressive as fewer and fewer Scrabble letters are left on the grid, and those that remain often passive-aggressively mute themselves. We are tired, but we know that the treadmill doesn’t have a stop button in a pandemic. Critic Martin Herbert, in an article for Art Review, describes the art world as ‘a perpetual-motion machine, or a tail wagging a dog’6 that suffocates us with content. Online degree shows are everywhere, providing new meat for curators to chew on. These virtual exhibitions are acutely designed profile pages with images and links, all tediously explained through long-winded captions and Zoom walkthroughs. The requirement for artists to simplify their works into neat conforming grids for the transitory viewer has prompted a backlash at the Royal College of Art, where I study. A group of students has set up an Instagram account called ‘@virtualshitshow2020’ that ridicules the concept by posting humorous memes and forthright opinions. Much of art, we are learning, remains steadfastly analogue at heart and is resisting being digitised for the pleasure of the acolytes of Zoom.

Running dry, lacking in energy and looking a little ho-hum – it has become glaringly obvious that Zoom and art education need to spend some time apart. The relationship has turned sour. What we briefly relished about it – that it was always there for us, with new treats and tricks to see – is precisely why it has become so tiresome. It’s time to take a step back and ‘go fishing’, in Martin Herbert’s words. Zoom was once simply a window through which to look at the world, but it has rapidly become a distorting prism and it's hard now to love what we see through it. Far from saving us from ruin, Zoom might, in fact, be it.

Learning from home, 2020

Manyu Jiang, The reason Zoom calls drain your energy, BBC Worklife, 22 April 2020.

Maureen Dowd, How to Look Good on Camera, According to Tom Ford, New York Times, 7 April 2020.

Paul O’Neill, The Culture of Curating and the Curating of Culture(s)(Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 4 May 2012.

Jens Hoffman and Maria Lind, ‘To Show or Not to Show’, Mousse Magazine, 5 December 2011.

Matt Blake, How to create the perfect background bookshelf, Penguin, 6 May 2020.

Martin Herbert, Gone Fishing, Art Review, 6 May 2020.